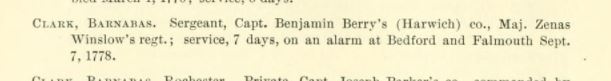

Sergeant Clark served in Major Zenas Winslow’s regiment. Major Winslow was the husband of Abigail Clark (1748-1830), Barnabas’ sister. In other words, Sergeant Barnabas Clark was a brother-in-law to his regimental commander. The Major would attain the rank of colonel during the Revolution.

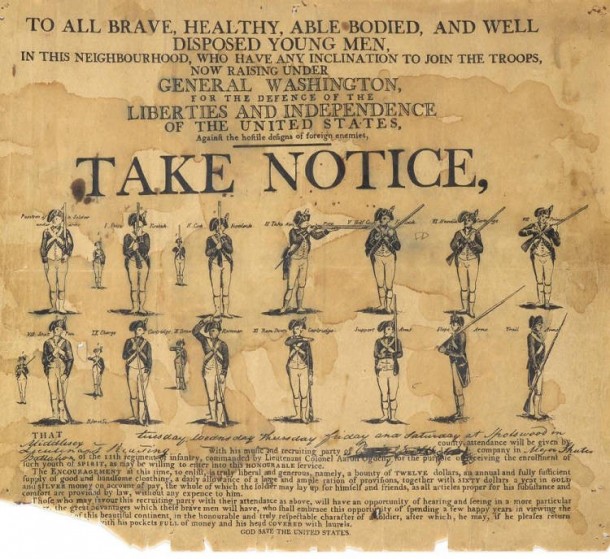

Major Winslow’s regiment included a company commanded by Captain Benjamin Berry, which operated in Harwich. Sergeant Clark was part of Berry’s company. Captain Berry was a surprising 67 years old in 1776, according to his 1709 Wenham, Massachusetts, birth record. Some genealogies describe him as an “elder revolutionary.” Captain Berry’s age implies the normally sedentary conditions of militia service. Although the “minute-men” companies of the militia were expected to rigorously train and prepare for rapid deployment, typical militia units like Barnabas Clark’s were rarely called to service outside their town.

Despite this, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War explains that Barnabas Clark served for seven days “on an alarm” at Bedford and Falmouth, Massachusetts, beginning on 7 September 1778. This alarm was in response to what has become known as Grey’s Raid – by British Major General Charles Grey. Under the pretense of relieving the British garrison at Newport, Rhode Island, Major General Grey conducted a series of raids on New Bedford, Fairhaven, and Martha’s Vineyard on 5-15 September 1778. Grey partially destroyed the town of Bedford on 5-6 September by setting fire to it, but was repelled the next day by the militia at Fairhaven.

Barnabas Clark’s militia in Harwich, located on Cape Cod to the east of Bedford and Fairhaven, would have first moved west to New Bedford and Fairhaven, and from there would have moved southeast to protect Falmouth as the British sailed in that direction. The British avoided a fight at Falmouth and instead kept sailing for Martha’s Vineyard. At Martha’s Vineyard, Major General Grey took 10,000 head of sheep.

In a Bicentennial study, author Sibyl Jerome described the militia’s actions at Fairhaven – highlighting the neighboring response force’s reluctant, but ultimately effective, defense of the town:

“On September 7, 1778, the British troops attempted to destroy the village of Fairhaven but were bravely repulsed by a small force commanded by Maj. Israel Fearing of Wareham. With the retreat of more senior officers, Maj. Fearing, now a Plymouth Brigade major, found himself in command. He was supported by men of other militia units in addition to those from Wareham.

“The enemy, a day or two previously, had burned houses and destroyed a large amount of property at New Bedford. From there they marched around to the head of the river to Sconticut Point, on the eastern side, leaving in their course, for some unknown reason, the villages of Oxford and Fairhaven. Here they continued until the following Monday, and then re-embarked.

“The following night a large body of them proceeded up the river, with a design to finish the work of destruction by burning Fairhaven. A critical attention to their movements had convinced the inhabitants that this was their intent, and induced them to prepare for their reception. The militia of the neighboring country had been summoned to the defense of the village.

“Their American commander [a colonel] was a man advanced in years. He determined that the place must be given up to the enemy, and that no opposition to the ravages of their town could be made with any hope of success. This decision of their commanding officer spread its benumbing influence over the militia, and threatened an absolute prevention of all enterprise. And, of course, threatened the ultimate destruction of this handsome village.

“Observing the torpor which was spreading among the troops, Maj. Fearing invited as many as had sufficient spirit to follow him and to station themselves at the post of danger. Among those who accepted the invitation was one of the elderly colonels, who, of course, became the commandant. But after they had arrived at Fairhaven, and the night had come, the colonel proposed to march the troops back into the country.

“He was warmly opposed by Maj. Fearing, and finding that he could not prevail, the elderly soldier prudently retired to a house three miles distant, where he passed the night in safety.

“After the colonel had withdrawn, Maj. Fearing, who was only 30 years at the time, but who was now commander-in-chief, arranged his men with activity and skill, and soon perceived the British approaching.

“The militia, already alarmed by the reluctance of their superior officers to meet the enemy, and naturally judging that men of years must understand the real state of the danger better than Maj. Fearing, a mere youth, were panic-struck at the approach of the enemy, and instantly withdrew from their posts.

“At this critical moment, Maj. Fearing, with the decision which awes men into a strong sense of duty, rallied them, and placing himself in the rear, declared, in a tone which removed all doubt, that he would kill the first man whom he found retreating.

“With the utmost expedition he led them to the scene of danger. The British had already set fire to several stores. Between these buildings, and throughout the village, Fearing stationed his troops, and ordered them to lie close in profound silence until the enemy, who was advancing, should have come so near that no marksman could easily mistake his object. The orders were punctually obeyed. “

Source: Wareham ’76: Revolution and Bicentennial, Sibyl Jerome, Kendall Printing, Inc., 1977, pp. 114-116.

Before Grey’s Raid, Massachusetts hadn’t been the location of Revolutionary War fighting for more than a year, and Massachusetts was spared from Revolutionary War battles afterwards – until the militia was called upon to support the July-August 1779 Penobscot Expedition. The revolutionaries sent a flotilla from Boston on 19 July 1779 for the upper Penobscot Bay in the District of Maine with a ground force of more than 1,000 Marines and militiamen. The Expedition’s goal was to reclaim control of mid-coast Maine from the British who had seized it a month earlier and renamed it New Ireland. There is no indication that Barnabas Clark participated in the Expedition, which resulted in a defeat for the US Navy. No known records exist to provide more detail of Barnabas’ service.

Barnabas Clark is listed with the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) as Ancestor #A022167. A DAR member, Lora Clark Gossard, was the first to claim Barnabas Clark as an ancestor, through our fifth-great grandmother Clarinda Sears (1795-1824). Clarinda Sears’s husband Atherton Clark (1789-1866) was the son of Barnabas Clark. A handful of other DAR members claim lineage to Barnabas Clark through another son, Alvan Clark (1771-1835).